Introducing: A new guest column series from Democracy & Society on the election of Javier Milei in Argentina.

In this series, authors submit commentary and analysis on Argentina’s 2023 election in which Javier Milei was elected President. Submissions in this series speak the economic situation, political environment, global waves of populism, and more. Below, Democracy & Society Junior Editor Paige Maylath draws on themes from each submission to introduce the topic and key elements of the recent election.

Paige Maylath

Reputable news sources have reported on Javier Milei’s electoral victory in 2023. Most pieces in this series discuss Jair Bolsonaro vis-a-vis Donald Trump, many making connections to the wave of right-wing populism sweeping across the globe and the concerning trend of democratic backsliding. These comparisons are worthwhile as they provide international context and inform how other world leaders will likely respond to Milei.

However, there is a risk of “over-contextualizing” this event and failing to properly recognize the political and economic factors unique to Argentina that may have led to Milei’s victory. The Justicialist (Peronist) Party (JP), whose candidate Milei defeated, has a long and rich history of using populist tactics and clientelism to assure electoral outcomes.[1] In our eagerness to incorporate Milei into the global trend of right-wing populism, we may overlook important patterns within Argentine politics like the consistent alternation between right-wing and left-wing governments. Milei’s election fits comfortably within that pattern. The Justicialist Party’s fiscal policy during the COVID-19 pandemic and failure to roll back spending after it ended has led to severe inflation and a marked decrease in economic growth. Economic hardship has severely impacted Argentine voters, and many blame the JP for the conditions they face.[2] Milei promised to take a “shock therapy”[3] approach to economic retrenchment during his campaign, and he has followed through on this promise in the months since he took office. He has cut government spending drastically and devalued the Argentine peso by over 54 percent.[4] These changes have caused massive price increases and wages are not keeping pace. In recent legislation, Milei hobbled labor unions, and he has threatened to withhold welfare benefits from those who participate in protests against his government.[5]

While the cyclical history of presidential elections in Argentina may predict a swing back to the left in a few years, Milei may find support and legitimacy from autocrats around the world that his predecessors did not have. Herein lies the value of context. Would-be autocrats around the world are borrowing from each other’s “playbooks” now. Autocratizing “strong men” frequently borrow each other’s tactics, and there are a few “plays” that we know to look out for that are early warnings of autocratization. These include attempts to manipulate or restrict the judiciary, crackdowns on press freedom, and policies aimed at marginalizing women and gender, ethnic, and religious minorities. As we monitor the longer-term impacts of Milei’s much-discussed economic policies, we must also pay attention to how he interacts with political institutions, particularly those that constrain his power.

[1] Auyero, Javier. “The Logic of Clientelism in Argentina: An Ethnographic Account.” Latin American Research Review 35, no. 3 (2000): 55–81. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2692042.

[2] Singerman, Eduardo. “Perón’s Legacy: Inflation In Argentina, An Institutionalized Fraud.” Forbes, January 30, 2015. https://www.forbes.com/sites/realspin/2015/01/30/perons-legacy-inflation-in-argentina-and-an-institutionalized-fraud/.

[3] The Economist. “Javier Milei Implements Shock Therapy in Argentina.” December 13, 2023. https://www.economist.com/the-americas/2023/12/13/javier-milei-implements-shock-therapy-in-argentina.

[4] Nicas, Jack, Natalie Alcoba, and Lucía Cholakian Herrera. “Argentina’s New ‘Anarcho-Capitalist’ President Starts Slashing.” The New York Times, December 13, 2023, sec. World. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/12/12/world/americas/argentina-javier-milei-cuts.html.

[5] Misculin, Nicolás. “Argentine Unions Raise Challenge to Milei with Major Strike, Protest.” Reuters, January 25, 2024, sec. Americas. https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/argentina-labor-union-holds-strike-biggest-challenge-yet-milei-2024-01-24/.

La Bronca: How Javier Milei Became the New President of Argentina

Alberto Maresca, M.A. Candidate in Latin American Studies, CLAS Georgetown University

After his outstanding electoral victory on November 19, 2023, the newly elected Argentinian President, Javier Milei, defined himself as the first “liberal-libertarian” to reach office.[1] Until recently, arguments on Milei were drawn on analogies to Trump and Bolsonaro, with whom he shares a conservative political worldview. On the other hand, it is worth noting that, unlike Trump and Bolsonaro, Milei is unbalanced in his social considerations, with contradictions like a quite liberal approach to marriage but opposition to abortion; he criticizes the Catholic Church but is quite conservative on gender and sexuality.[2] It is important to remember that since the Argentinian primary elections, the PASO, held in August 2023, in which Milei was the most voted, he was defined as a far-right candidate.[3] His politically incorrect methodology played a significant role: The more he received critiques from the media or his political rivals, the bigger his consensus grew. Why did that happen? Because Argentinian voters, during this election, had a single and clear priority: to solve the economic crisis with any alternative to the current government.

Milei’s ideology is anti-everything. Despite the doubtable feasibility of his projects related to selling the Argentinian Central Bank or dollarizing the economy, his condemnation of the “political caste” – including the former President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, the incumbent Alberto Fernández and his direct opponent in the run-off, the last Minister of Economy, Sergio Massa – has been crucial for appealing to voters.[4] It is essential to understand how Milei earned 55.7% votes, against the 44.3% obtained by Sergio Massa. Young Argentinians between ages 16 and 34 composed the pillar of Milei’s victory in the run-off.[5] This demographic, an active and dynamic labor force, has been the most affected by Argentinian inflation. Young Argentinians have directly felt the mismanagement of the various governments since 2007 and even earlier if we consider those who lived through the 2001 crisis. Specifically, the economic effects of COVID-19 motivated even more Argentinians to move abroad to the rest of the Americas or Europe.[6] Hence, this sector of the Argentinian population not only paid the price of the peso currency devaluation but also witnessed an unprecedented emigration, leading them to see Milei as the only alternative to the political class responsible for the national decline. Their vote is not ideological nor identitarian, as in the case of Trump and Bolsonaro. It is instead a vote of protest and rage, or bronca as it is labeled in Argentina.

During the first round of elections, held in October 2023, Sergio Massa prevailed over Milei. This defeat caused an agreement between Milei’s La Libertad Avanza and Juntos por el Cambio, a conservative coalition around former President Mauricio Macri, which was seen as a betrayal of Milei’s claimed antagonism to all establishments.[7] This was only relevant for Peronist politicians, who tried to merge such discourse with the risks of Milei’s presidency in terms of destruction of the public sector and undermining of democracy forty years after Argentina recuperated its democratic system. All those speeches sound like nothing more than the wind to voters whose worries are primarily the economy and personal security. The evidence can be found in the aftermath of the last presidential debate, in which an unprepared Milei had to counter Massa’s broad knowledge of the state machine. However, to voters, Massa represented the Minister of Economy for a country with 140% inflation, whose understanding of the public system confirmed his guilt, being perceived as corrupted and involved as any other politician.[8]

In other words, Milei’s victory is an anti-political choice created by the public fatigue with political and economic failures by Argentinian politicians. Milei must now become a politician in all senses, having to deal with Congressional compromises and trying to avoid for himself the sentiment that drove his election: La bronca.

[1]. “Javier Milei dice ser un ‘liberal libertario’: ¿qué significa?,” CNN en Español, November 20, 2023, https://cnnespanol.cnn.com/2023/11/20/liberal-libertario-javier-milei-en-que-consiste-orix-arg/.

[2]. Thomas Kestler, “Radical, Nativist, Authoritarian—Or All of These? Assessing Recent Cases of Right-Wing Populism in Latin America,” Journal of Politics in Latin America 14, no. 3 (December 1, 2022): 289–310, https://doi.org/10.1177/1866802X221117565.

[3]. Nicolás Misculin, Eliana Raszewski, and Candelaria Grimberg, “Argentine Far-Right Outsider Javier Milei Posts Shock Win in Primary Election,” Reuters, August 14, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/argentina-set-primary-vote-with-ruling-peronists-fighting-survival-2023-08-13/.

[4]. Jonas Bugtene Boulifa, “Paper Promises: The Effects of Inflation on Social Life in Buenos Aires, Argentina” (Master thesis, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, 2023), https://ntnuopen.ntnu.no/ntnu-xmlui/handle/11250/3080014.

[5]. Borja Andrino and Montse Hidalgo Pérez, “Mapa | ¿Quién ha votado a Milei? Así son sus apoyos por edad, género o territorio,” El País, November 21, 2023, https://elpais.com/argentina/2023-11-21/mapa-quien-ha-votado-a-milei-asi-son-sus-apoyos-por-edad-genero-o-territorio.html.According to El País and Encuestas Atlas, being the latter among the most recognized pollsters in Latin America, Milei’s voting intentions for Argentinians between 16-24 was 69% of the interviewed, 20% for Sergio Massa, while in the range 25-34, the 54% was for Milei and the 41% for Massa.

[6]. Josefina Gil Moreira and Natalia Louzau, “‘Chau Argentina’. Cuántos fueron, qué edad tienen y qué países eligieron los argentinos que decidieron emigrar,” La Nación, July 12, 2023, https://www.lanacion.com.ar/sociedad/chau-argentina-cuantos-fueron-que-edad-tienen-y-que-paises-eligieron-los-argentinos-que-decidieron-nid07072023/.

[7]. “‘Acuerdo con la casta’: Kicillof habló de la ‘traición’ de Macri, Bullrich y Milei por el balotaje,” Buenos Aires Noticia, October 31, 2023, https://buenosairesnoticia.com.ar/nota/3490/acuerdo-con-la-casta-kicillof-hablo-de-la-traicion-de-macri-bullrich-y-milei-por-el-balotaje/.

[8]. Mariano Schuster and Pablo Stefanoni, “El Huracán Milei Siete Claves de La Elección Argentina,” Nueva Sociedad, November 20, 2023, https://nuso.org/articulo/el-huracan-milei/.

Democracy and Populism coexisting: Milei’s election is just another day for Argentina’s democracy

Pedro Huet

When analyzing the victory of Javier Milei, many analysts appeal to Argentina’s recent history. In general, it follows similar trends to many Latin American countries: political instability during the early 20th century, decades of military dictatorships, uneasy democratization at the end of the century, and an upsurge in populism during the 21st century.[i] Argentina, like several other Latin American states, has seen a cyclical election of presidents who employ a left-wing populist rhetoric, followed by others who employ a right-wing approach, or vice versa.[ii] Although many scholars have focused on these trends to analyze the country’s current democratic situation, few have focused on a unique quality of the country’s political system: the coexistence of democracy and populism.

The term populism can be defined as a political strategy in which a personalistic leader seeks or exercises government power based on support from a large number of unorganized followers, via a charismatic quasi-personal connection with them[iii]. It is often accompanied by a confrontational rhetoric that accuses the incumbent government of being corrupt and caters to an idealized popular identity. Due to the incendiary nature of its rhetoric and its reliance on a single figure, it tends to divide the population (i.e. the just against the corrupt), allows the populists to abuse their political influence, and results in the enactment of what is considered politically and economically extreme[iv]. Given how deleterious to social stability these effects can be, it is unsurprising that these controversial politicians and their movements often cause a severe erosion of democracy by replacing democratic institutions with strong nationalist ideas and a cult-like loyalty to charismatic political figures.[v]

In Argentina, however, we see different effects compared to other countries. Elsewhere, populist movements erode democracy, but in Argentina they seem to coexist. During the greater part of the 20th century, the country experienced a series of coup d’états that brought unstable military juntas into power. During this period, populist politicians, like Juan Domingo Peron, were the only leaders capable of implementing democratic processes in the country for a limited amount of time.[vi] Decades later, when the junta regimes were discredited and the country’s elites committed to adhering to democratic processes, it was these strong, unconventional and charismatic populist leaders that played a key role in preserving democracy. For example, Carlos Menem and Nestor Kirchner, amassed high approval ratings and support for their elected platforms at times in which most Argentine households were facing economic hardships and seemed to be questioning the effectiveness of the new political system, nurturing popular representation in the country.[vii] Last year, we saw a general election in which an incumbent and his opponent used populism to appeal to the masses with their incendiary rhetoric and harsh criticisms. The process resulted in Argentina’s government being again shaped by a democratic transition: the winner was named president of Argentina and the loser accepted the results.[viii]

This is not to say that populist politicians in Argentina have not taken detrimental actions to the country’s democracy. However, transitions of power in Argentina after 1983 have followed a consistent trend: the party in power responds to the population’s choice above the disruptive ideas, messages and personalities of their representatives.

This implies political sophistication among Argentine voters: they may be treating populist rhetoric as simply another characteristic of a candidate, considering it as any other trait, economic policy, political ideology, track-record, and so on. Argentine voters are not blinded by the promises or the cult of these leaders, so politicians can´t fall back on this technique to stay in office. There are various signs that populists in power have not severely damaged the country’s democratic process, be it due to unwillingness or inability. On one hand, the last three General Argentine Elections (2015, 2019 and 2023) have seen peaceful democratic transitions of power between opposing parties, which means that the electorate’s choice decides who governs. One the other hand, staunch international democracy measures, such as the Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy Index, display Argentina’s democracy score mostly unchanged during the last seventeen years, actually showing a slight increase (3%) in democracy during said time period[ix]. This could very well imply that, in Argentina, democratic elections are seen as the only game in town.[x]

Given this trend, we should expect that Javier Milei’s election and presidency will likely be just another chapter in Argentina’s democratic history. If his unorthodox policies[xi] don’t improve the country’s precarious economic position, voters will likely penalize him if or when he seeks a second term.

[i] Nicolás Cachanosky and Alexandre Padilla, “Latin American Populism in the Twenty-First Century”, The Independent Review, 24(2) https://www.jstor.org/stable/45216633, 210 – 214.

[ii] Carolina Salgado and Paula Sandrin, “Pink Tide”then a“Turn to the Right”: Populisms and extremism in Latin America in the twenty‐first century” In B. De Souza Guilherme, C. Ghymers, S. Griffith‐Jones, & A. RibeiroHoffmann (eds.), Financial crisis management and democracy (266 – 268), Springer International Publishing, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-54895-7_17

[iii] Kurt Weyland, “Clarifying a Contested Concept: Populism in the Study of Latin American Politics”, Comparative Politics 34, no. 1 (2001): 12 – 14. https://doi.org/10.2307/422412.

[iv] Pippa Norris and Ronald Inglehart, “Understanding Populism.” In Cultural Backlash: Trump, Brexit, and Authoritarian Populism (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2019), 10 – 12. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108595841

[v] Christian Houle and Paul D. Kenny, “The Political and Economic Consequences of Populist Rule in America”. Government and Opposition 53(2), (2018), 279 – 280. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/government-and-opposition/article/political-and-economic-consequences-of-populist-rule-in-latin-america/DF3D269BA3D964CCDED5B07B0EA380B5?utm_campaign=shareaholic&utm_medium=copy_link&utm_source=bookmark

[vi] Enrique Peruzzotti, “Peronism and the Birth of Modern Populism.” Journal of Inter-Regional Studies: Regional and Global Perspectives (JIRS), vol 2, 2019, pp. 5 – 6, https://www.waseda.jp/inst/oris/assets/ uploads/2018/03/04_Peronism-and-the-Birth-of-Modern-Populism_ Enrique-Peruzzotti.pdf

[vii] María Fernanda Arias, “Charismatic Leadership and the Transition to Democracy: The Rise of Carlos Saul Menem in Argentine Politics”, Texas Papers on Latin America, 95(2), (1995), Working Paper, https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/items/ae24a976-d560-43a6-8681-03d7b3eb6bd2

[viii] Nicolas Misculin, “ Argentina President-elect Milei meets outgoing Fernandez after election win”, Reuters, November 21, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/argentina-president-elect-milei-meets-outgoing-fernandez-after-election-win-2023-11-21/

[ix] Economist Intelligence Unit, Democracy Index 2022: Frontline democracy and the battle for Ukraine. Retrieved from http://www.gapm.io/dxlsdemocrix on February 2, 2023.

[x] Juan José Linz and Alfred C Stepan. “Toward Consolidated Democracies”, Journal of Democracy, 7(2), (1996), 14-15. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.1996.0031.

[xi] Javier Baez, “ Milei proposes paying salaries in Argentina with Bitcoin, meat and even milk”, News Breezer, December 25, 2025, https://newsbeezer.com/mexicoeng/milei-proposes-paying-salaries-in-argentina-with-bitcoin-meat-and-even-milk/

Javier Milei: Invasiveness in a New Age of Argentine Politics

Joaquin Amigorena is an Argentine-Mexican-American undergraduate student at the George Washington University Elliott School of International Affairs, with regional concentrations in Latin America and East Asia.

Introduction

The November 19th Argentine runoff election provides a sobering outlook on Argentina’s political landscape. In an electoral upset, Peronist incumbents were convincingly ousted from the Casa Rosada – not by their traditional rivals, as represented by Patricia Bullrich’s Juntos por el Cambio (JxC) – but by political newcomer Javier Milei, leader of the hyper-libertarian, alt-right La Libertad Avanza (LLA). When framing Milei within the power dynamics and political culture that have defined Argentina post-Guerra Sucia, it becomes clear that the new political leader bears a policy vision that is deeply invasive within Argentine politics. This invasiveness is critical in understanding his ascent to the presidency, the institutional obstacles likely to come his way, and his turbulent potential to reshuffle the norms of Argentine Democracy.

Pre-existing Political Culture

Traditionally, Argentina’s political arena has been contested by two broad political factions: the center-right, led most recently by Juntos por el Cambio, and the more powerful Peronist coalition, a left-leaning, albeit ideologically chameleonic political movement with deep ties to organized labor.[i] Barring three presidential administrations, Peronist politicians have entrenched themselves in Argentina’s presidential system by creating a subsistence relationship between a bloated, interventionist state and the Argentine citizenry. Their ratification of protectionist, redistributionist, and subsidy policies, while having bolstered popular support and economic growth in the short-term, exacerbated national debt, hyperinflation, and institutional corruption in the long run.[ii] [iii] [iv] While center-right opponents have provided policy alternatives centered around moderate austerity reforms, tempered public spending, and relaxed labor codes, Peronists have historically weaponized the working class’s dependency on these policies to effectively antagonize attempts at changing the status quo.[v]

Invasive Policy Alternative

Milei’s entry into Argentina’s political arena gave the Argentine electorate an invasive third choice, a scorched earth approach in dealing with its bloated state. In campaign rallies and now-viral social media posts, the politician called for the dismantling of the central bank, the closure of key government departments, and the privatization of state-owned enterprises; Milei had essentially called for the radical deconstruction of an Argentine state 80 years in the making.[vi] [vii] Milei’s electoral momentum –particularly among middle class and young male voters – was clearly a testament to the economic desperation felt by the Argentine citizenry, amidst a poverty and inflation rate of 40% and 140% respectively.[viii] [ix] It also underlined voter’s newly-held conviction that the policy alternatives offered by the “casta política” – or pre-existing political establishment – could no longer achieve much-needed, transformative change.

Institutional Obstacles

While Milei’s invasiveness was key in his rise to the Argentine presidency, it is now deterring his ambitious policy agenda while in power. Within the Argentine National Congress, Milei’s LLA holds only thirty-eight of two-hundred-fifty-seven seats in the Chamber of Deputies, and seven of seventy-two seats in the Senate.[x] To push legislation, LLA must caucus, and by extension, incorporate the policy-input of the center-right, inevitably posing constraints on the more fringe components of Milei’s policy vision. Milei is facing similar challenges when tackling Argentina’s federalist system, in which LLA holds zero governorships. This is particularly troubling when considering that provincial governors are allotted an omnipotent, caudillo-like reign over local institutions and policy enforcement. Their compliance typically requires huge swathes of government funding, a dynamic antithetical to Milei’s budget-slashing agenda.[xi] Tensions between LLA, the National Congress, and provincial governors were most recently highlighted by the Chamber of Deputies’ rejection of Milei’s ‘omnibus’ law – a massive 646-article bill designed to honor the president’s promise of dismantling elements of the Argentine state and restarting the economy via shock therapy. According to the administration, the bill’s failure was at the hands of ‘traitorous’ lawmakers from the center-right and the external sabotage of Argentine governors.[xii] Nationwide labor strikes, incited by Peronists and their union allies, pose a similar threat to the administration.[xiii] Milei and LLA’s positioning as a political newcomer, while attractive for a disgruntled electorate, is clearly a weakness when facing Argentina’s political institutions and the political parties entrenched within them.

Dissention from Democratic Norms

Milei’s political capital largely stems from his transformative economic proposals, yet an analysis of the figure cannot ignore his divisive stances on social issues inextricably tied to the norms of Argentine democracy. One of the foundational pillars of post-dictatorship Argentina has been the collective denunciation of the Military’s gross human rights record during the Guerra Sucia – a period of state terrorism inflicted by the Argentine military junta [1974-1983]. This has accordingly led to the removal of the defense establishment as a meaningful actor in domestic politics. On the campaign trail, Milei sharply dissented from this precedent, employing revisionist rhetoric that downplayed atrocities committed and venerated the role of the military.[xiii] LLA has also recently proposed legislation that would reverse Argentina’s legalization of abortion, challenging a set of legislative accomplishments centered around gender equality laws and women’s rights that have defined Argentine democracy.[xv] While institutional obstacles and political opposition may be sufficient in blocking legislative outcomes, Milei’s legitimization and platforming of these fringe viewpoints threatens to corrode the public’s faith in Argentina’s democratic norms.

Conclusion

When comparing Milei’s policy vision to Argentina’s party establishment, institutions, and democratic norms, it becomes clear that the figure represents a turbulent, invasive force within Argentine politics. While this invasiveness could be seen as a conduit for transformative change, it may be hampered by Argentina’s institutional realities and serve as a warning sign for continued political volatility, historical revisionism, and democratic backsliding. Only time – something of which Milei’s governing mandate has very little off – can tell.

[i] Ocampo, Emilio. “What Kind of Populism Is Peronism?” Serie Documentos de Trabajo, Universidad del Centro de Estudios Macroeconómicos de Argentina (UCEMA), Buenos Aires, 732, 2020, 12. https://doi.org/https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/238357/1/732.pdf.

[ii] Fontevecchia, Agustino. “Argentina: Cristina Kirchner, Macri and Alberto Fernández – All of Them Took on Debt.” Forbes, January 19, 2021. https://www.forbes.com/sites/afontevecchia/2021/01/21/argentina-cristina-kirchner-macri-and-alberto-fernndez–all-of-them-took-on-debt/?sh=143903f54272.

[iii] Martinez, Adan. “Argentina: A Consumer Subsidy Trap.” Center for Latin American & Caribbean Studies, December 21, 2022. https://clacs.berkeley.edu/argentina-consumer-subsidy-trap.

[iv] Salama, Pierre. “Economic Growth and Inflation in Argentina under Kirchner’s Government.” SSRN Electronic Journal, 2011, 167-168. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2140229.

[v] Gedan, Benjamin N. “Opinion: Much of Argentina Wants Its Populists Back.” NPR, August 10, 2019. https://www.npr.org/2019/08/10/748419903/opinion-much-of-argentina-wants-its-populists-back.

[vi] Buenos Aires Herald. “Milei Reveals First Privatization Plans as President-Elect.” Buenos Aires Herald, November 20, 2023. https://buenosairesherald.com/economics/milei-reveals-first-privatization-plans-as-president-elect.

[vii] Nacion, La. “El Video Viral de Tiktok Donde Javier Milei Revela Qué Ministerios Dejaría ‘Afuera’ Si Llega a Ser Presidente.” LA NACION, August 15, 2023. https://www.lanacion.com.ar/politica/el-video-viral-de-tiktok-donde-javier-milei-revela-que-ministerios-dejaria-afuera-si-llega-a-ser-nid15082023/.

[viii] “can’t buy new jeans”: Argentina inflation hits 143% as shoppers …, November 13, 2023. https://www.reuters.com/business/retail-consumer/cant-buy-new-jeans-argentinas-100-inflation-draws-crowds-used-clothes-markets-2023-11-13/.

[ix] “Incidencia de La Pobreza y La Indigencia En 31 Aglomerados Urbanos.” Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas y Censos , September 27, 2023. https://www.indec.gob.ar/uploads/informesdeprensa/eph_pobreza_09_2326FC0901C2.pdf.

[x] Jütten, Marc. “Argentina: Outcome of the 2023 Elections – Beginning of a New Era?: Think Tank: European Parliament.” Think Tank | European Parliament, November 2023. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document/EPRS_ATA(2023)754610.

[xi] Kingstone, Peter. “Carlos Scartascini, Ernesto H. Stein and Mariano Tommasi, Eds., How Democracy Works: Political Institutions, Actors, and Arenas in Latin American Policymaking. Washington, DC: Inter-American Development Bank, 2010. Tables, Bibliography, Index, 333 Pp.; Paperback $29.95.” Latin American Politics and Society 54, no. 1 (2012): 207–9. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1531426x00000108.

[xii] Centenera, Mar. “Argentina’s Javier Milei Declares War on the Opposition after His Mega-Bill to Dismantle the State Is Rejected.” EL PAÍS English, February 7, 2024. https://english.elpais.com/international/2024-02-07/argentinas-javier-milei-declares-war-on-the-opposition-after-his-megalaw-to-dismantle-the-state-is-rejected.html.

[xiii] Soltys, Martin. “Protests, Strikes, Unions ‘on Alert’: Unrest against Milei’s Government Grows.” Buenos Aires Times, February 23, 2024. https://batimes.com.ar/news/argentina/strikes-in-different-sectors-and-the-cgt-in-a-state-of-alert-the-first-73-days-of-mileis-government.phtml.

[xv] Grinspan, Lautaro. “Will Milei Rewrite Argentina’s History?” Foreign Policy, December 14, 2023. https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/12/14/argentina-milei-dictatorship-junta-memory-human-rights/.

[xvi] EFE, Agencia. “Milei’s Party Presents Draft Bill to Repeal Argentina Abortion Law.” EFE Noticias, February 8, 2024. https://efe.com/en/latest-news/2024-02-08/mileis-party-presents-draft-bill-to-repeal-argentina-abortion-law/.

On dead center: Milei’s trap for the center parties in Argentina

Francisco M. Olivero

Milei’s election has captured quite an audience. An economist and TV commentator who arrived at power with libertarian anarcho-capitalist ideas, he’s raised suspicion of democratic backsliding. Milei is a democratic leader if we consider a minimalist definition of democracy[i]. He won free and clean elections, following every step required by the Argentinian electoral law, and was recognized as the legal winner by his opponents[ii]. However, the concern is a degradation of the maximalist idea of democracy[iii] as well as the institutional watchdogs. Przeworski [iv] uses an example that clarifies this point:

“Declaring the advent of democracy in Spain, Adolfo Suarez proclaimed that henceforth ‘The future is not written because only people can write it’. (…) But people can write whatever they happen to want. Democracy does not guarantee anything other than that is the people who would write the future”.

In this way, Argentinians decided that Milei would be the main author of the future chapter, but this will be a coauthored one. We must consider the two other political forces: the Peronist party and the ‘center coalition.’ The former is a well-known opposition that is currently enthralled in a renovation process. It is the main representative of a corporatist economy[v] and the principal adversary of Milei’s economic plan. The second is not a standing coalition but a group of parties with left-center, center, and right-center ideology. These include the Radical Party (UCR), the Civic Coalition (Coalición Cívica – ARI), The Republican Purpose (PRO) ‘moderates’ group, and several minor provincial parties controlled by Governors from ‘The Interior.’ The administration is now forced by the balance of power to form policy coalitions.

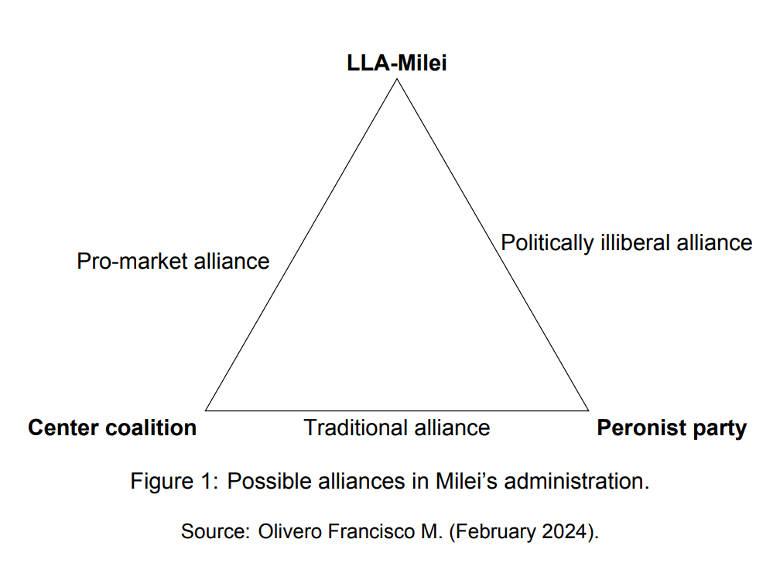

Figure 1 classifies and names the possible alliances that the three main legislative and political actors (Milei, Center Coalition, and Peronism) can develop. The first one is the Politically illiberal alliance, which may be triggered if the current administration attempts any measures to weaken vertical or horizontal accountability, akin to the recent proposals made by the Peronist party, including media reform or court impeachment. The second one is the Traditional alliance – dubbed “traditional” as UCR and PJ, two established parties, will serve as its leaders – could be the main opposition to stop Milei’s aggrandizement. The last and most likely alliance to form is a Pro-market alliance, which not only allows for economic reforms, but also suggests that the center coalition has a dual challenge: one related to policy and the other to elections. This is what I call the ‘double-level dilemma’ of the center parties[vi].

For several years, the center coalition tried to carry out a series of reforms to guarantee macroeconomic balance.[vii] However, their institutionalist goal and their economic agenda clashed following the recent election loss. On one hand, they can support the government and carry out an economic agenda more like their preferences. On the other hand, they want to stop Milei’s aggrandizement for two reasons: 1) it implies a loss of legislative power at the hands of the executive power, and 2) for the center coalition’s normative preference toward liberal democracy.[viii] Thus the expected outcome will be a function of repeated interactions and choices made by both the opposition and the incumbent.[ix] Nonetheless, each move Milei makes to consolidate his power will result in the opposition losing an institutional check on his misuse of executive authority and vice versa.

In parallel, the ‘center coalition’ faces a second dilemma at the electoral level. They decided not to be the main opposition and left this place to the Peronist party. Consequently, they must escape from an electoral trap. Should they collaborate with Milei and his administration to achieve the economic goals of inflation reduction and growth, the center coalition will probably not have any electoral benefit. Rather, it will result in an increase in Milei’s popularity and, maybe, in an electoral victory of the incumbent in the midterm elections. Alternatively, if they work with Milei but the economy does not improve, the center alliance will likely be perceived as ‘collaborationist’ and the Peronist Party will have the opportunity to gain both economic and punitive votes[x]since it will be viewed as the “true opposition.”

Finally, the economic crisis and Milei’s popularity created a social desire for quick action, which conflicted with the time needed to work out policy agreements. Alliances and negotiations will be intrinsic in the next two years. However, predictions of ‘democratic alarms’ remain about the center coalition, the double-level dilemma that could cause the center to deteriorate. This may be seen as signs of impending democratic crisis,[xi]ultimately deepening polarization between Milei and the Peronist party due to fears of losing votes to the extremes.[xii]

[i] Przeworski, Adam; Alvarez, Michael R.; Cheibub, José Antonio; & Limongi, Fernando. 2000. “Democracy and Development: Political Institutions and Well-being in the World, 1950-1990” (New York, Cambridge University Press).

Schumpeter, Joseph A. 1942. “Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy”. New York: Harper & Brothers.

[ii] For full pre-requisited see: Dahl, Robert. 1971. “Polyarchy: Participation and Opposition”. New Haven: Yale University Press.

[iii] Miller, S.M., Martin Rein, Pamela Roby, and Bertram M. Gross. 1967. “Poverty, Inequality, and Conflict”. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 373 (2): 16−52.

Ringen, Stein. 2007. “What Democracy Is For”. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Daniels, Norman. 1990. “Equality of What: Welfare, Resources, or Capabilities”. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 50: 273-296

[iv] Przeworski, Adam. 2024. “Defending Democracy”. Accessed January 2024. Available at SSRN.

[v] See the discussion: O’Donnell, Guillermo. 1977. “Estado y Alianzas en Argentina: 1956-1976”. Desarrollo Económico, 64: 523-554.

Gerchunoff, Pablo, and Rapetti, Martín. 2016. “La economía argentina y su conflicto distributive structural (1930-2015)”. El Trimestre Económico, LXXXIII(2)(330): 225-272. México: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Etchemendy, Sebastián. 2019. “The Rise of Segmented Neo-Corporatism in South America: Wage Coordination in Argentina and Uruguay (2005-2015)”. Comparative Political Studies, 52(10): 1427-1465.

Vommaro, Gabriel. 2019. “Estado y Alianzas…, cuarenta años después. Elementos para pensar el Giro a la Derecha en Argentina”. Revista de Ciencias Sociales, 32(44): 43-60.

Schipani, Andrés. 2021. “Despertando al gigante invertebrado: la estrategia sindical de los gobiernos kirchneristas (2003-2015)”. Revista SAAP, 15(2): 389-419.

Etchemendy, Sebastián. 2023. “40 Años De Democracia: Lo Viejo Y Lo Nuevo En La Política De Los Ciclos Económicos Argentinos”. Desarrollo Económico. Revista De Ciencias Sociales 63 (240):143-54.

[vi] Inspired in: Putnam, Robert D. 1988. “Diplomacy and Domestic Politics: The Logic of Two-Level Games.” International Organization 42, no. 3: 427–60.

[vii] Gerchunoff, Pablo, and Llach, Lucas. 2010. “El Ciclo de la Ilusión y el Desencanto: un siglo de políticas económicas argentinas”. Emecé.

Sturzenegger, Federico. 2019. “Macri’s Macro: The meandering road to stability and growth”. Working paper 135. Universidad de San Andrés, Departamento de Economía. Revised Oct 2019.

[viii] Mainwaring, Scott; and Pérez Linán, Aníbal. 2019. “Democracias y dictaduras en América Latina. Surgimiento, supervivencia y caída”. Ciudad de México: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

[ix] Cleary, Matthew R., and Aykut Öztürk. 2022. “When Does Backsliding Lead to Breakdown? Uncertainty and Opposition Strategies in Democracies at Risk.” Perspectives on Politics 20, no. 1: 205–21.

[x] Luna, Juan Pablo, and Rovira Kaltwasser, Cristóbal. 2021. “Castigo a los oficialismos y ciclo político de derecha en América Latina”. Revista Uruguaya de Ciencia Política, 30(1): 135-156.

[xi] Levitsky, Steven, and Daniel Ziblatt. 2019. “How Democracies Die”. Harlow, England: Penguin Books.

Przeworski, Adam. 2019. “Potential Causes.” Chapter. In Crises of Democracy, 103–22. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[xii] Downs, Anthony. 1957. “An Economic Theory of Political Action in a Democracy.” Journal of Political Economy 65, no. 2 (1957): 135–50.

Populism, Patronage, and COVID-19: An economic history perspective on Milei’s election

Yifan Chen

President Javier Milei’s rise to Argentine federal politics is seen as unprecedented. Since 2003, there has only been one candidate elected to the presidency who was not from the two main political parties, Partido Jursticialista and Union Civica Radical.[i] Throughout his 2023 candidacy, Milei campaigned on a platform of dollarization, a closer relationship to the United States, the elimination of the country’s central bank, and cutting high government spending to tackle Argentina’s soaring inflation and poverty.[ii] Most importantly, he argued that the previous administrations were single-handedly responsible for Argentina’s current economic crisis.[iii]

The election of a far-right libertarian and anti-establishment candidate in Argentina may seem to represent an ideological shift in the populace and raise concern about democratic backsliding. However, in Argentina, politics are more likely affected by economic outcomes from trade, clientelism, and patronage than ideology and partisanship.[iv] Using a historical analysis of Argentina’s federal economic policy since 2003, Milei’s election can be seen less as an ideological shift in the populace, but more so a manifestation of the public’s frustration with Argentina’s current economic outlook and patronage politics.

Argentina’s economy historically experienced profound shocks from the Global Financial Crisis in 2007 and again in 2012. The economy’s fragility has been exacerbated by policies enacted by husband-and-wife establishment leaders Néstor Kirchner and Cristina Fernández de Kirchner (CFK), both preeminent presidents from 2003 to 2015.[v] They “overvalued the exchange rate to subsidize consumption”[vi] and, in turn, nationalized private pension funds for them to be distributed at the executive’s discretion, garnering political support through patronage. Over the long term, however, the overvalued exchange rate weakened the trade account balance. Argentina’s exports were more expensive for foreign buyers, while imports became cheaper to purchase, damaging the competitiveness of the domestic industry.[vii] Even an increase in subsidies for domestic industry was unable to match losses. Public spending for pension coverage, cash-transfer schemes, and other subsidies to gather public support increased, but tax revenue, important for funding these redistributive projects, decreased due to falling exports.[viii]

As a result, center-right politician Mauricio Macri, who promised economic growth while dismantling CFK’s systems of corruption and patronage, won the 2015 election in an upset that ended twelve years of Kirchernist governance.[ix] Initially, Macri was set up to be a much-needed change in stabilizing economic conditions across the country: international financial markets “embraced” his market-oriented policies and financed 4% of GDP in 2016 and 2017.”[x] However, Macri then changed inflation targets, which offset the trade benefits of the devalued peso. Macri’s term as the first right-wing candidate since 2003 is certainly an anomaly in Argentine politics but follows the established pattern of economic outlook and patronage affecting voter preference in presidential elections. Poor economic conditions in the international market and decreased purchasing power undermined faith in Macri’s policies, leading to the return of Kirchnerism through the election of Alberto Fernández and his vice president CFK in 2019.[xi] Short-term considerations of economic progress, rather than partisanship, were the most important factor in these elections. Voters selected Macri because they believed CFK’s corruption and economic policies failed them, and the same base of voters ousted him when his policies also failed.[xii]

Shortly into Fernández’s term in office, the COVID-19 pandemic struck. Given the federal government’s reliance on the established system of patronage through gains from exports, the pandemic was extremely detrimental to his and his party’s popularity. Fernández enacted redistributive policies simultaneously to garner political clout and support distressed industries, but inflation rose too quickly for these policies to be effective.[xiii] High government spending and fiscal imbalances, combined with structural inflationary pressures from the pandemic, caused inflation to skyrocket. By the 2023 presidential elections, the inflation rate increased to 142.7% in October 2023.[xiv]

The return of Kirchnerism, as represented by the Fernández administration, and its ultimate failure to spur economic growth or stability meant that it was no longer a solution for the Argentine people. Instead, it became representative of a corrupt and incompetent economic and political elite that was out of touch with the devastating realities of poverty in Argentina. While the public was already dissatisfied with the Kirchners’ economic policies, the persistent failure of the same systems created a structural distaste. In this sense, Milei’s election was not unprecedented. After two decades of an incumbent party that relied on economic policies that fed on structural corruption and patronage,[xv] Milei’s rhetoric of fundamentally ridding Argentina of Peronism was appealing. No matter how controversial his policies are, they struck at the core the frustrations that voters then felt. Milei’s popularity will only continue if he can access the material resources necessary to distribute benefits to key interest groups while spurring economic growth and correcting inflation,[xvi] all of which are daunting tasks. After Milei’s inauguration, he backtracked on some of his radical economic policies, including his stance on dollarizing the peso to control inflation.[xvii] Ultimately, if he is unable to create a positive economic outlook, Milei’s popularity as a president may decline.

[i] Lupu, Oliveros, and Schiumerini, Campaigns and Voters in Developing Democracies: Argentina in Comparative Perspective, 31.

[ii] La Libertad Avanza, “La Libertad Avanza: Bases de Acción Política y Plataforma Electoral Nacional,” 2.

[iii] Schmidt, “Argentina’s New Far-Right President Promises Shock to the System.”

[iv] Lupu, Oliveros, and Schiumerini, Campaigns and Voters in Developing Democracies: Argentina in Comparative Perspective, 40.

[v] Peña and Barlow, “Beyond the Boom.”

[vii] Richardson, “Export-Oriented Populism,” 238.

[ix] Sturzenegger, “Yes, Macri Failed on the Economy. But It Wasn’t All for Naught.”

[xii] Rossi, “Democratorship in Argentina.”

[xiii] Rathi, “Argentina’s Endless Economic Crisis Sends Inflation Soaring.”

[xv] Richardson, “Export-Oriented Populism,” 238.

[xvi] Misculin, “In Setback for Argentina’s Milei, Sweeping Reform Bill Sent Back to Committee.”