by Jean F. Crombois

The decision, made in June 2022, to grant Ukraine and Moldova candidate status to EU accession puts into question the EU enlargement policy. The new geopolitical situation caused by the unprovoked and illegal aggression of Ukraine by Russia calls for a complete revamping of the EU enlargement policy.

The accession of Moldova and Ukraine, while still leaving the question open for Georgia, will mostly depend on the outcome of the War in Ukraine; it should not lead to a new stalemate as far as the Western Balkans are concerned.

EU enlargement policy has shown its limits as a possible vector for reforms in the candidate countries. At the same time, the erosion of rule of law within the European Union itself calls into question the dividing lines between candidate countries and EU member states in this respect. There is, therefore, a compelling need for the EU to revisit its conditionality and to transform it from an external tool for transformation into an internal tool to strengthen the rule of law and respect for fundamental freedoms within the European Union.

- The Limits of Conditionality

The concept of conditionality has been developed in the context of the EU enlargement to Central and Eastern European countries. Such conditionality takes the form of setting legal, political, and economic conditions for EU accession. In short, the conditions to be accepted as a candidate country are set by Article 49 of the Treaty of the European Union, such as being a European state abiding by the EU’s values regarding the rule of law and fundamental freedoms. Once candidate status is granted, another set of criteria, referred to as the Copenhagen criteria defined in 1993, apply for EU accession. These consisted of political criteria in terms of the rule of law, fundamental freedoms, and protection of minorities; economic criteria of being able to sustain the competitive pressure of the internal market; legal criteria linked with the need to transpose existing EU legislation into national legislation and also settling of disputes with their neighbors.

The main principles of these conditions are rooted in designing a system by which candidate countries’ governments would be rewarded if they comply with these conditions and to withhold such reward in case of failing to comply with them.[i]

That being said, scholars have noticed that conditionality may quickly become a ‘power consumable resource.’[ii] In other words, once a candidate country joins the European Union, there is little leeway left for the EU to address shortcomings in terms of ongoing reforms. To address such issues, the EU designed ex-post accession mechanisms for monitoring the rule of law situation in the new member states, as in the cases of Bulgaria and Romania. This system has since been replaced by the EU monitoring of the rule of law in all the EU member states. That being said, any conditionality has its limits in terms of inducing deeply rooted transformations in the candidate countries, as the cases of Bulgaria and Romania showed. Moreover, conditionality cannot ignore the geopolitical stakes of EU enlargement policy.

2. The Geopolitics of EU Enlargement

When taking office in 2019, the new President of the EU Commission, Ursula Von der Leyen, announced her willingness to have a geopolitical Commission. This announcement did confirm a new emphasis on geopolitics in EU external policies. That new emphasis became already visible in the aftermath of the EU-Russia crisis of 2014, reminding the EU of the resurgence of power politics in Europe. If anything, the COVID-19 crisis in the Western Balkans highlighted the extent to which the region has once again become a space for renewed competition between the great powers.[iii]

In its involvement in the Western Balkans, the EU has portrayed itself as a major transformative force or, as some scholars called it, a transformative power. In this light, EU policies are aimed at guiding the reform process in the candidate countries through setting accession conditions referred to as accession conditionality and Europeanization, a process by which adaptation to the EU becomes deeply intertwined with domestic policy-making and providing them substantial financial support.

Since 2016-2017, the EU has gradually shifted to a new geopolitical approach in its involvement with the Western Balkans. This shift is being translated into some key documents related to EU foreign policy, such as the new 2016 EU Global Strategy with a stronger emphasis on EU interests, stability, resilience, and the need to develop defense capabilities. Related more specifically to EU enlargement, the 2018 Commission’s Enlargement Strategy, while not giving up on its transformative dimensions, uses new words and concepts alluding to the Western Balkans as being part of the EU’s sphere of interests: “EU membership for the Western Balkans is in the Union’s very own political, security and economic interest.”[iv]

If the 2018 new EU Enlargement strategy emphasized the need for reforms in human rights and good governance, the 2020 Enlargement methodology gives more say to the member states in assessing the situation in the countries concerned. This greater political steer may well go both ways: either in the direction of a tougher approach or a more lenient approach according to the foreign policy preferences of the member states concerned. In any case, the use of unanimity in these decisions may well lead to other deadlocks as member states can always use enlargement decisions as a way to settle political scores with the candidate countries, as reflected in the Bulgarian veto, in November 2020, to start accession negotiations with North Macedonia. That decision affected Albania whose accession path was linked to North Macedonia.[v]

3. Western Balkans Accession Process

If the Western Balkan leaders officially expressed their support for the granting of EU candidate status to Moldova and Ukraine, they also deplored the fact that Bosnia was still kept in the cold, not to mention the stalemate regarding the start of accession negotiations with North Macedonia. Only later, in December 2022, was Bosnia granted candidate status while Kosovo submitted its application, and a way out from the deadlock situation regarding North Macedonia was reached.

On paper, the decision regarding Moldova and Ukraine does not fundamentally affect the path for EU accession for the Western Balkans. First, the decision was considered as more symbolic than anything. Secondly, it occurred when EU enlargement to the Western Balkans had been losing momentum. There are certainly multiple reasons for this situation. From an EU point of view, the succession of crises it was confronted with contributed to reverting the issue to the back burner. Paradoxically enough, the fact that the region has largely remained stable did not generate any sense of urgency for the EU to act decisively.[vi]

Yet, the EU did not remain completely inactive. EU leaders, such as the German Chancellor, toured Southeastern Europe in August 2022 with a positive message about their EU accession. In December, the EU-Western Balkan Summit took place for the first time in the region, in Tirana, where the EU leaders renewed their commitments to EU accession for the Western Balkans while offering them a new financial package of up to 1 billion Euros to help them mitigate the effect of the energy crisis. The Summit also underlined the geopolitical reasons for the EU to be more engaged in the Western Balkans to counter rising Russian and Chinese influence in the region. But if some have viewed the Summit as a sign that EU enlargement has been revived, others have remained much more circumspect.[vii]

The crucial question, besides one of neighbourly disputes such as the one between Bulgaria and North Macedonia, remains the extent to which the Western Balkan candidates fulfill the EU conditions for EU accession, especially in terms of the rule of law, fundamental freedoms, and the fight against corruption and organized crime. In this respect, all the countries have had little if no improvements since 2014-2015. New concepts such as the one of “backsliding’ or “de-democratization” were introduced to describe the situation in the Western Balkans as far as rule of law and fundamental freedoms were concerned.[viii]

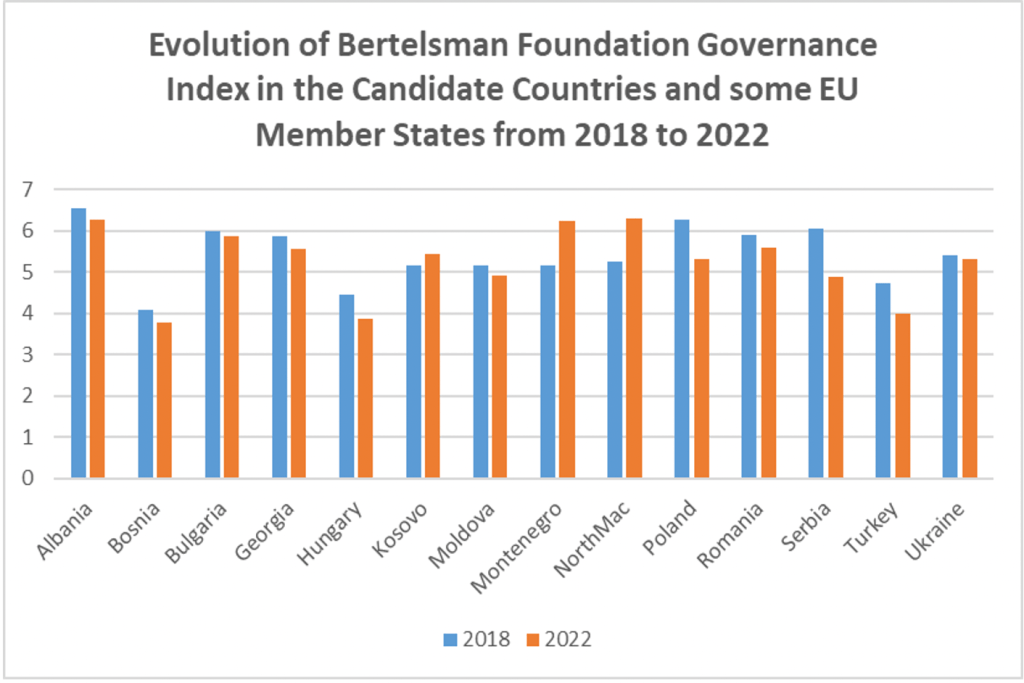

However, the focus on the rule of law and fundamental freedoms in the Western Balkans should not divert attention on the evolution within some EU member states in the same domains. Based on the indexes designed by the Bertelsmann Foundation[ix], the situations in some EU member states such as Hungary, Poland, Bulgaria, Romania and in the Western Balkan candidate countries, not mentioning the Eastern European candidate countries, do not differ that much; and in some cases, EU member states, such as Hungary, scored below these countries [see graph below].

These results raise the question of the impact of the EU conditionality as an external tool for domestic transformations in the candidate countries and the need to develop new internal conditionality to counter any further backsliding within the European Union itself.[x]

On the foreign policy front, the Western Balkans, with the exceptions of Serbia and Bosnia, aligned themselves on the EU sanctions regime adopted to Russia. But here again, such commitments, also asked by some member states such as the Netherlands as a new condition for accession, clash with the position of Hungary, which has been more than reluctant to fully adhere to the EU decisions regarding Russia, if not try to block or water them down. [xi]

In other words, the accession process has drawn dividing lines in Europe that have become increasingly artificial. Indeed, in terms of performances regarding the rule of law and fundamental freedoms, not to mention foreign policy, these lines do not reflect significant differences between some EU member states and the candidate countries.

In this context, any delay in the accession process may reveal increasingly expensive for the EU, geopolitically speaking. Regarding domestic reforms, the longer the accession process lasts, the more likely it will further undermine pro-liberal forces in the Western Balkans. In terms of geopolitics, it will most certainly contribute to strengthening the negative influence of external powers, such as Russia, and even Turkey and China.

4. Ending the Purgatory

The new geopolitical situation created by the war in Ukraine calls for the EU to clarify its ambitions towards the Western Balkans. Indeed, if the war taught us anything it is that EU enlargement has become highly geopolitical.[xii]

In other words, the EU must choose between two options: 1) either it decides to strengthen relations with these countries willing to do so, leading to the question of their EU accession in a relatively short prospect, starting with the Western Balkans, 2) or the EU continues to insist on its transformative agenda with a risk of an ever-delayed EU accession for the same countries.

The discussions on the readiness or not of the Western Balkans and of Moldova and Ukraine also conceal a critical dimension which is the one of erosion, within the EU, of the very fundamental principles of the rule of law and fundamental freedoms. On the geopolitical front, the EU has much to lose if it continues to delay EU accession for the Western Balkans, and will find it increasingly difficult to rally the support of public opinion for EU membership. Such a delay would also contribute to strengthening the influence of Russia in the region with all its destabilizing effects on their national societies.

As a possible solution, some leading Brussels-based think-tankers suggested the concept of staged integration that would allow the candidate countries to take advantage of some of the EU policies in a rather short term, and to move from there to an accession stage that would give them voting rights, short of veto rights and the possibility of having one Commissioner.[xiii]

There are strong geopolitical reasons for speeding up the accession process for the Western Balkans. At the same time, there is a need to strengthen the internal dimensions of respect for the rule of law and the principles of fundamental freedoms within the European Union. This could lead to replace the use of EU conditionality as an external tool that showed its limitations into an internal one. Such a logic would prevent the Western Balkans from being locked indefinitely in EU accession purgatory.

Jean F. Crombois is Associate Professor of European Studies at the American University in Bulgaria. He has published on many EU issues such as the EU’s Eastern Partnership and EU enlargement both in academic venues as well as for news outlets in Belgium and in France.

[[i]] Szarek-Mason, Patrycja. “Conditionality in the EU Accession Process.” Chapter. In The European Union’s Fight Against Corruption: The Evolving Policy Towards Member States and Candidate Countries, 135–56. Cambridge Studies in European Law and Policy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010. https://doi:10.1017/CBO9780511676086.005

[[ii]] Smith, Karen E., ‘The Evolution and Application of EU Membership Conditionality’, in Marise Cremona (ed.), The Enlargement of the European Union (Oxford, 2003; online ed, Oxford Academic. 2012), https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199260942.003.0005

[[iii]] Rustemi, Arlinda [et alt]. Geopolitical Influences of External Powers in the Western Balkans. The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies, 2021. https://hcss.nl/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Geopolitical-Influences-of-External-Powers-in-the-Western-Balkans_0.pdfhttps://hcss.nl/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Geopolitical-Influences-of-External-Powers-in-the-Western-Balkans_0.pdf

[[iv]] European Commission. A credible enlargement perspective for and enhanced EU engagement with the Western Balkans, 6 February 2018, 1. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:d284b8de-0c15-11e8-966a-01aa75ed71a1.0001.02/DOC_1&format=PDF

[[v]] Cvijic, Sdrjan, Ditching unanimity is key to make enlargement work, 4 February 2019 [Euractiv. Com]. Retrieved from: https://www.euractiv.com/section/enlargement/opinion/ditching-unanimity-is-key-to-make-enlargement-work/

[[vi]] Bechev, Dimitar. What has stopped EU Enlargement in the Western Balkans [Carnegie Europe] 20 June 2022. https://carnegieeurope.eu/2022/06/20/what-has-stopped-eu-enlargement-in-western-balkans-pub-87348

[[vii]] Bancroft, Ian. Is There Really New Momentum Behind EU Enlargement?, BalkanInsight 13 March 2023. https://balkaninsight.com/2023/03/13/is-there-really-new-momentum-behind-eu-enlargement/

[[viii]] Bieber, Floran. Introduction. In: The Rise of Authoritarianism in the Western Balkans. New Perspectives on South-East Europe. Palgrave Pivot, 2020, 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-22149-2_1

[[ix]] Governance in the BTI refers to the quality of political management in transformation processes. We examine a country’s political decision-makers and take structural difficulties into account. The index value is derived from the performance in four governance components multiplied by a factor that is determined by the country’s individual level of difficulty. https://bti-project.org/en/index/governance

[[x] ]Kmezić, Marko & Bieber, Floran. Protecting the rule of law in EU Member States and Candidate Countries, SIEPS, October 2020.https://www.sieps.se/globalassets/publikationer/2020/2020_12epa.pdf?

[[xi]] Dunai, Marton. Bad blood between Hungary and Ukraine undermines EU unity on Russia. Financial Times, 1 July 2023. https://www.ft.com/content/61abd814-d4bb-4e68-853e-f2e5d7be6c9e

[[xii] ]Barber, Tony. Growing pains of EU enlargement, Financial Times, 19 June 2023. https://www.ft.com/content/bc3af28e-84be-44c7-875a-25ee50244395?desktop=true&segmentId=d8d3e364-5197-20eb-17cf-2437841d178a#myft:notification:instant-email:content

[[xiii]]Meister, Stefan, Nis, Milan, Kirova, Iskra & Blockmans, Steven. Russia’s War in Ukraine: Rethinking the EU’s Enlargement and Neighborhood Policy [DGAP Report, 1, 2023). https://dgap.org/en/research/publications/russias-war-ukraine-rethinking-eus-eastern-enlargement-and-neighborhood