Francisco M. Olivero

Milei’s election has captured quite an audience. An economist and TV commentator who arrived at power with libertarian anarcho-capitalist ideas, he’s raised suspicion of democratic backsliding. Milei is a democratic leader if we consider a minimalist definition of democracy[i]. He won free and clean elections, following every step required by the Argentinian electoral law, and was recognized as the legal winner by his opponents[ii]. However, the concern is a degradation of the maximalist idea of democracy[iii] as well as the institutional watchdogs. Przeworski [iv] uses an example that clarifies this point:

“Declaring the advent of democracy in Spain, Adolfo Suarez proclaimed that henceforth ‘The future is not written because only people can write it’. (…) But people can write whatever they happen to want. Democracy does not guarantee anything other than that is the people who would write the future”.

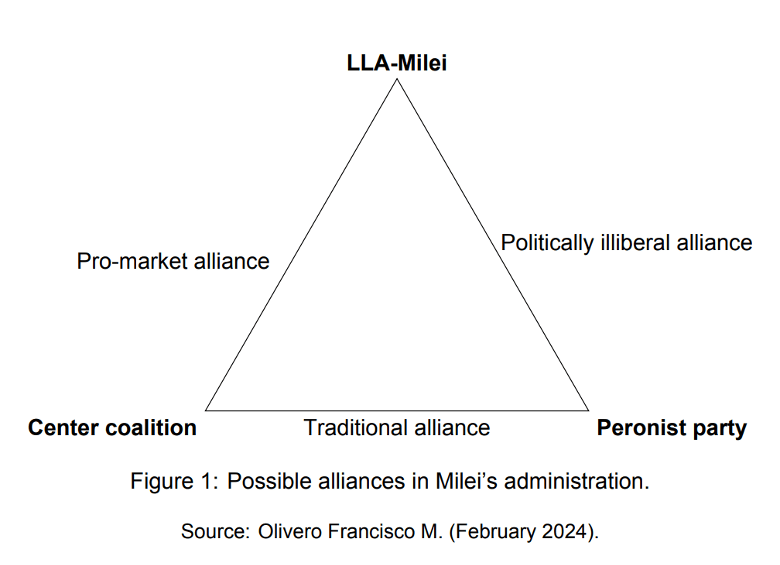

In this way, Argentinians decided that Milei would be the main author of the future chapter, but this will be a coauthored one. We must consider the two other political forces: the Peronist party and the ‘center coalition.’ The former is a well-known opposition that is currently enthralled in a renovation process. It is the main representative of a corporatist economy[v] and the principal adversary of Milei’s economic plan. The second is not a standing coalition but a group of parties with left-center, center, and right-center ideology. These include the Radical Party (UCR), the Civic Coalition (Coalición Cívica – ARI), The Republican Purpose (PRO) ‘moderates’ group, and several minor provincial parties controlled by Governors from ‘The Interior.’ The administration is now forced by the balance of power to form policy coalitions.

Figure 1 classifies and names the possible alliances that the three main legislative and political actors (Milei, Center Coalition, and Peronism) can develop. The first one is the Politically illiberal alliance, which may be triggered if the current administration attempts any measures to weaken vertical or horizontal accountability, akin to the recent proposals made by the Peronist party, including media reform or court impeachment. The second one is the Traditional alliance – dubbed “traditional” as UCR and PJ, two established parties, will serve as its leaders – could be the main opposition to stop Milei’s aggrandizement. The last and most likely alliance to form is a Pro-market alliance, which not only allows for economic reforms, but also suggests that the center coalition has a dual challenge: one related to policy and the other to elections. This is what I call the ‘double-level dilemma’ of the center parties[vi].

For several years, the center coalition tried to carry out a series of reforms to guarantee macroeconomic balance.[vii] However, their institutionalist goal and their economic agenda clashed following the recent election loss. On one hand, they can support the government and carry out an economic agenda more like their preferences. On the other hand, they want to stop Milei’s aggrandizement for two reasons: 1) it implies a loss of legislative power at the hands of the executive power, and 2) for the center coalition’s normative preference toward liberal democracy.[viii] Thus the expected outcome will be a function of repeated interactions and choices made by both the opposition and the incumbent.[ix] Nonetheless, each move Milei makes to consolidate his power will result in the opposition losing an institutional check on his misuse of executive authority and vice versa.

In parallel, the ‘center coalition’ faces a second dilemma at the electoral level. They decided not to be the main opposition and left this place to the Peronist party. Consequently, they must escape from an electoral trap. Should they collaborate with Milei and his administration to achieve the economic goals of inflation reduction and growth, the center coalition will probably not have any electoral benefit. Rather, it will result in an increase in Milei’s popularity and, maybe, in an electoral victory of the incumbent in the midterm elections. Alternatively, if they work with Milei but the economy does not improve, the center alliance will likely be perceived as ‘collaborationist’ and the Peronist Party will have the opportunity to gain both economic and punitive votes[x]since it will be viewed as the “true opposition.”

Finally, the economic crisis and Milei’s popularity created a social desire for quick action, which conflicted with the time needed to work out policy agreements. Alliances and negotiations will be intrinsic in the next two years. However, predictions of ‘democratic alarms’ remain about the center coalition, the double-level dilemma that could cause the center to deteriorate. This may be seen as signs of impending democratic crisis,[xi]ultimately deepening polarization between Milei and the Peronist party due to fears of losing votes to the extremes.[xii]

[i] Przeworski, Adam; Alvarez, Michael R.; Cheibub, José Antonio; & Limongi, Fernando. 2000. “Democracy and Development: Political Institutions and Well-being in the World, 1950-1990” (New York, Cambridge University Press).

Schumpeter, Joseph A. 1942. “Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy”. New York: Harper & Brothers.

[ii] For full pre-requisited see: Dahl, Robert. 1971. “Polyarchy: Participation and Opposition”. New Haven: Yale University Press.

[iii] Miller, S.M., Martin Rein, Pamela Roby, and Bertram M. Gross. 1967. “Poverty, Inequality, and Conflict”. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 373 (2): 16−52.

Ringen, Stein. 2007. “What Democracy Is For”. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Daniels, Norman. 1990. “Equality of What: Welfare, Resources, or Capabilities”. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 50: 273-296

[iv] Przeworski, Adam. 2024. “Defending Democracy”. Accessed January 2024. Available at SSRN.

[v] See the discussion: O’Donnell, Guillermo. 1977. “Estado y Alianzas en Argentina: 1956-1976”. Desarrollo Económico, 64: 523-554.

Gerchunoff, Pablo, and Rapetti, Martín. 2016. “La economía argentina y su conflicto distributive structural (1930-2015)”. El Trimestre Económico, LXXXIII(2)(330): 225-272. México: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Etchemendy, Sebastián. 2019. “The Rise of Segmented Neo-Corporatism in South America: Wage Coordination in Argentina and Uruguay (2005-2015)”. Comparative Political Studies, 52(10): 1427-1465.

Vommaro, Gabriel. 2019. “Estado y Alianzas…, cuarenta años después. Elementos para pensar el Giro a la Derecha en Argentina”. Revista de Ciencias Sociales, 32(44): 43-60.

Schipani, Andrés. 2021. “Despertando al gigante invertebrado: la estrategia sindical de los gobiernos kirchneristas (2003-2015)”. Revista SAAP, 15(2): 389-419.

Etchemendy, Sebastián. 2023. “40 Años De Democracia: Lo Viejo Y Lo Nuevo En La Política De Los Ciclos Económicos Argentinos”. Desarrollo Económico. Revista De Ciencias Sociales 63 (240):143-54.

[vi] Inspired in: Putnam, Robert D. 1988. “Diplomacy and Domestic Politics: The Logic of Two-Level Games.” International Organization 42, no. 3: 427–60.

[vii] Gerchunoff, Pablo, and Llach, Lucas. 2010. “El Ciclo de la Ilusión y el Desencanto: un siglo de políticas económicas argentinas”. Emecé.

Sturzenegger, Federico. 2019. “Macri’s Macro: The meandering road to stability and growth”. Working paper 135. Universidad de San Andrés, Departamento de Economía. Revised Oct 2019.

[viii] Mainwaring, Scott; and Pérez Linán, Aníbal. 2019. “Democracias y dictaduras en América Latina. Surgimiento, supervivencia y caída”. Ciudad de México: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

[ix] Cleary, Matthew R., and Aykut Öztürk. 2022. “When Does Backsliding Lead to Breakdown? Uncertainty and Opposition Strategies in Democracies at Risk.” Perspectives on Politics 20, no. 1: 205–21.

[x] Luna, Juan Pablo, and Rovira Kaltwasser, Cristóbal. 2021. “Castigo a los oficialismos y ciclo político de derecha en América Latina”. Revista Uruguaya de Ciencia Política, 30(1): 135-156.

[xi] Levitsky, Steven, and Daniel Ziblatt. 2019. “How Democracies Die”. Harlow, England: Penguin Books.

Przeworski, Adam. 2019. “Potential Causes.” Chapter. In Crises of Democracy, 103–22. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[xii] Downs, Anthony. 1957. “An Economic Theory of Political Action in a Democracy.” Journal of Political Economy 65, no. 2 (1957): 135–50.

Leave a reply to On dead center: Milei’s trap for the center parties in Argentina – Francisco Olivero Cancel reply